Employment reports usually get a lot of attention, but they might have lost some of their importance as economic data points.

Today we’ll suggest that common job numbers may have become more of lagging indicators than leading indicators. It’s worth considering this week, given some of the big announcements like ADP’s private-sector payrolls on Wednesday and non-farm payrolls on Friday.

It’s also important because we’ve all heard for a long time that the job market is “the best in years.” Americans on unemployment benefits are at their lowest levels in almost five decades! Available positions outnumber job seekers for the first time ever! The unemployment rate is also at long-term lows! Amazing!

The numbers have remained very positive — almost like the proverbial broken record — while other reports have struggled. Home construction, for instance, is imploding. Retail sales have failed deliver any big upside surprises since the spring. Ditto for durable-goods orders.

So here’s a thought: What if there are longer-term cycles when the economy creates more jobs than others? What if we’re simply in a period that’s been more favorable to workers? Data from the Labor and Commerce Departments suggests this might actually be the case.

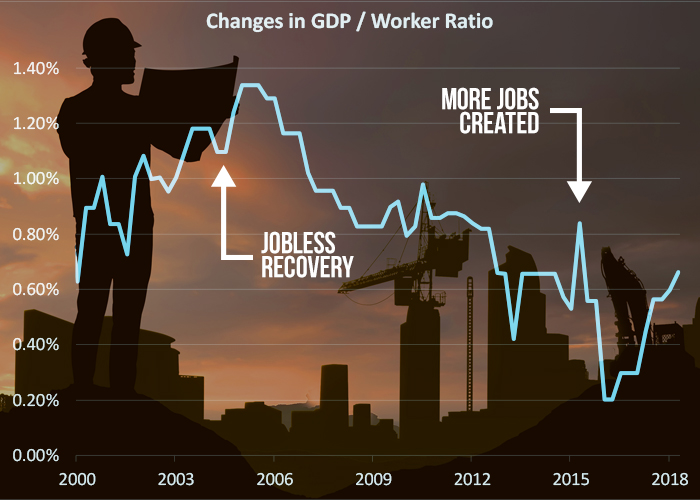

I lined up all the data since 1947 and calculated the ratio between gross domestic product to non-farm payrolls. (Lower numbers are “good” for workers because it means more jobs were created per unit of GDP.) Then I looked at the change between quarters. The results are telling.

The ratio increased about 0.2 – 0.5 percent per quarter since early 2015. (GDP barely outpaced job gains.) That’s a huge contrast with the previous economic expansion between 2002 and 2007, when the GDP/payrolls ratio typically grew more than 1 percent per quarter. (GDP outpaced job gains by a wide margin.)

Then consider how last decade was a “jobless recovery.” The broader economy rebounded and companies made record profits, while many Americans felt left behind. My GDP/payrolls ratio clearly shows how this was the case.

It also makes sense when you think about businesses using technology and globalization to get more efficient. Remember all those productivity gains everyone kept talking about under Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan? This is what it looked like.

But what if the pendulum swung too far? What if there were no more workers to be cut by early this decade? That would explain the steady growth of employment and decline of jobless claims we’ve seen more recently.

In other words, companies might have cut “too many jobs” in the 2002-2007 period, leaving them “behind the curve” more recently. If that’s the case — as my chart suggests — it would mean that employment’s now more of a lagging indicator than a leading indicator.

This could be important because typically investors and traders place a lot of emphasis on reports like this week’s non-farm payrolls. But other numbers like rail traffic have recently painted a different picture. For now, jobs could be taking a back seat to those.